In the July-August 1998 issue of the Harvard Business Review, authors B. Joseph Pine II and James H. Gilmore introduced what they termed “the experience economy,” the concept that positioned experiences as the next category of economic value in the progression of economic history.

“An experience is not an amorphous construct; it is as real an offering as any service, good or commodity.”

In the July-August 1998 issue of the Harvard Business Review, authors B. Joseph Pine II and James H. Gilmore introduced what they termed “the experience economy,” the concept that positioned experiences as the next category of economic value in the progression of economic history.

It was titled “Welcome to the Experience Economy.” Welcome indeed—since the publication of their formative article and the game-changing book that followed a year later, the experience economy has fully arrived.

The following is an overview of the fundamental ideas these two thinkers introduced and refined with the book’s updated 2011 edition. It is easy to see why their proposition is more relevant to business than ever—and the special role real estate plays in providing the spaces in which the congregant experiences the authors focus on can be enacted.

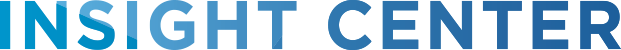

The Progression of Economic Value

“Commodities are fungible, good tangible, services intangible, and experience memorable.”

Pine and Gilmore identify in their article the three economic distinctions that are widely accepted—commodities, goods, and services. The authors then add a fourth category to this evolution: the post-services economic category of experiences.

Economists have historically lumped experiences in with services, but as Pine and Gilmore note, “Experiences are a distinct economic offering, as different from services as services are from goods. Today we can identify and describe this fourth economic offering because consumers unquestionably desire experiences, and more and more businesses are responding by explicitly designing and promoting them.”

The authors famously used the birthday cake as the central signifier of the emerging experience economy—particularly the shift from commodities (the core ingredients of a homemade birthday cake like flour, sugar, and eggs) to goods (a Betty Crocker mix purchased at the grocery store) to services (the birthday cake bought at the grocery store bakery, decorated by an anonymous employee instead of dear old mom) to experiences (the now-common “outsourced” birthday party using a rented, themed space, catered food, and, of course, a birthday cake).

The authors note that experiences have traditionally been at the heart of the entertainment business, as entertainment has always been uniquely capable of providing memorable experiences. But the experience economy is about much more than being entertained—because an experience provides something unique to each individual, its impact is determined at an individual level: “[E]xperiences are inherently personal, existing only in the mind of an individual who has been engaged on an emotional, physical, intellectual, or even spiritual level. Thus, no two people can have the same experience, because each experience derives from the interaction between the staged event…and the individual’s state of mind.” (To read about this concept as it applies to today’s waterparks, read our Insight Center piece Innovation Brings New Experiences to Waterparks.)

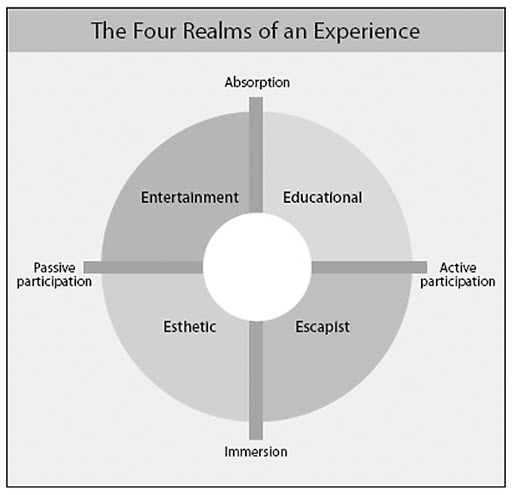

“The Four Realms of an Experience”

“The Four Es” as defined by Pine and Gilmore are entertainment plus the educational, escapist, and esthetic realms of experience. As seen below, absorption and immersion are one variable, and active vs. passive participation the second variable. Within these four touchpoints, the varieties of experience occur.

The authors describe experience as existing across two dimensions: customer participation (which can include active or passive participation, or anything in between these two poles) and connection, or environmental relationship, that unites customers with the event or performance. This connection can be characterized by absorption or immersion.

Because an experience acts on each individual person differently, an experience is always customized and never mass produced, meaning it is inherently personal, authentic, and meaningful for the one experiencing it. Recognizing this distinction is what allows businesses to customize and differentiate their value proposition for their guests, which is of vital importance as supply continually outpaces demand for mass produced goods, while spending on experiences steadily increases.

The Natural Role of Real Estate

“Today the concept of selling experiences is spreading beyond theaters and theme parks.”

The work of Pine and Gilmore has proved transformative in its implications for business. But underpinning the complexities of their theories is a basic need for spaces in which to enact the values of this shifting economy. Experiences are inherently tied to spaces and places, and real estate provides the settings necessary for consumers (or “guests”) to cultivate their unique memorable experience.

In the real estate industry, the essential measure of success is the occupancy rates of given properties. Retail properties have been notably adjusting to the shift in consumer behavior and spending, with retail landlords steadily adding more experience-based properties to their holdings and/or modifying existing properties and business models to align with the cultural shift.

According to the authors, “It is vital that more experiences in the future be available only by admission, for such holds the key to a full-fledged Experience Economy. What truly makes an experience a distinct economic offering, providing new sources of revenue growth, is requiring customers to explicitly pay for the time they spend in places or events.”

Admissions-based attractions are often the property types analysts of the experience economy examine closely. Pine and Gilmore also urge businesses to consider how their offerings would change if they charged admission. This prompting is intended to provoke a deeper attenuation to the inherent differentiation point of a business’s offering, which can then be refined and improved.

Expanded amenity theatres provide another example of the impact of the experience economy. What seems contradictory—the removal of seats in a movie theatre to make room for larger, more luxurious seats—has led to markedly improved attendance and revenues for theatre operators. This means that there are less people per theatre, yet the change results in increased spend per theatre and per seat. How does this make sense? The experience of going to the movies being clearly identified as a critical focus for operators, who are enhancing the moviegoing experience by offering such items like luxury seating, expanded food and beverage options, and premium digital technology. (Read about how the “dynamic in-theatre experience” impacts the bottom line in 5 Reasons Why 2015 Was a Record Year for the Box Office or The Customer Experience Evolution.)

The Economy of Experience vs. the Economy of Stuff: The Significance of Millennials

“One of the largest generations in history is about to move into its prime spending years. Millennials are poised to reshape the economy; their unique experiences will change the ways we buy and sell, forcing companies to examine how they do business for decades to come.”

Coinciding with the work of Pine and Gilmore is the demographic shift in which millennials became the leading cohort in terms of overall population and therefore consumer spending.

The most recent data from the U.S. Census Bureau shows that Millennials outnumber baby boomers in overall population (83 million to 75.4 million), putting them in the lead as consumers and influencers of wider consumer behaviors and trends. As we discussed in our prior Insight Center article Millennials: Shaping a New Economy of Experience, Millennials are leading the way in the experience economy as a generation that overwhelmingly (78%) prefers access to goods over ownership of goods.

The spending habits of Millennials reflect a belief that while material goods might provide temporary pleasure or display status to others, investing in experiences means an investment in a good that can’t be compromised by a challenged economy—as well as a memory that won’t disappear in a volatile market or in the face of sudden unemployment, both situations that Millennials faced upon coming of age. Experiences that can be enjoyed in the moment, shared with friends and loved ones, and recalled after the fact as pleasant memories are new models for consumer behavior largely introduced by Millennial values. (Find out how Family Entertainment Centers have evolved to meet these shifts in Not Your Father’s FEC: New Concepts Keep Family Entertainment Centers Fresh.)

But the experience economy is not limited to this newer demographic. The “grey market,” as the “over-60s” were recently termed in a recent Economist article, currently spend some $4 trillion a year, and are similarly interested in spending their hard-earned golden years busy having experiences. As the Economist reported, “research on older people suggests they are less eager to acquire material possessions than preceding generations and much keener to acquire experience, particularly through travel and study.”

The Key: Ongoing Business Innovation

Pine and Gilmore make clear that experience is the vital link between a business and its potential audience or “guests.” The authors propose that ultimately the experience economy will unfold through ongoing business innovation, “which threatens to render irrelevant those who relegate themselves to the diminishing world of goods and services.”

For further reading on this topic, the influential Harvard Business Review article is available in full here, or order the latest edition of the book.