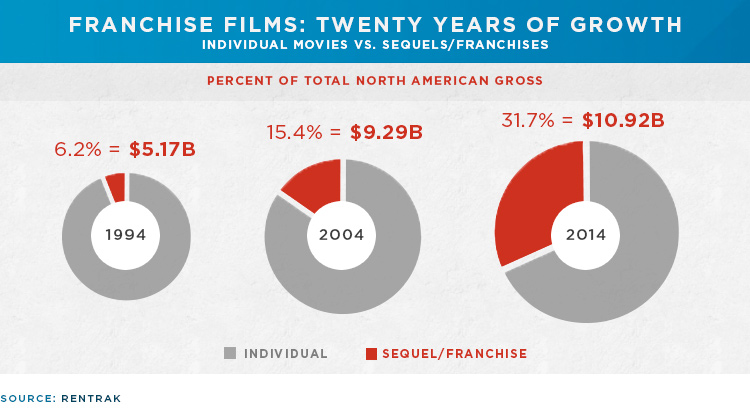

This August, North American box office revenue hit a record high for year-to-date, with analysts predicting a record-breaking finish to 2015.

Most credit this box office success to the franchise films that comprise most of this year’s top revenue generators, with Jurassic World, Avengers: Age of Ultron, Furious 7, and Minions included in the count. The current record for annual box office revenue of $10.92B was set in 2013 and is also attributed to the franchise films that dominated that year.

Movies outside of the franchise model continue to see box office success as well: Pixar’s “Inside Out” came in third at the box office this summer, and Universal’s “Straight Outta Compton” made five times its $28 million budget to become the most successful music biopic of all time. Though the production of franchise films has been rising steadily over the last twenty years, their box office impact seems sudden. But the model for the success of these movies originated with studio executives eager to create a slate in which all of their movies would thrive.

Within the industry, it is largely agreed that the 1975 movie Jaws was the first true summer blockbuster, and its success meant that the summer, typically reserved for the anticipated failures of a studio’s roster, was suddenly a time frame studios were eager to optimize. Its unusually wide release, sustained marketing campaign, and cross-promotional merchandising created a box office event no one anticipated. Its success also set the stage for the refined strategy franchise films would later employ.

The Strategist Behind the Franchise Film Model

The leap from blockbuster film to film franchises wasn’t an organic evolution. The industry shift is commonly attributed to one man: Alan Horn, current Chairman of the Walt Disney Studios. In a New York Times piece from 2011, Horn is called “the guy who drafted the blueprints for what [became] Warner’s primary operating strategy — focusing on effects-filled event pictures, or ‘tent poles,’” that have the potential to resonate overseas as well as domestically. This strategy worked so well for Warner Bros. that it is now the template for most major studios aiming to bring predictability to the unique entertainment marketplace.

Beginning in 1999, Horn slated 4 or 5 of these tent pole films a year, with the intention they would carry the studio’s 20 or so other productions on their back. These 4 or 5 films would receive the bulk of the studio’s production budget and extensive marketing and promotion. By 2011, Warner Bros. had set a record by becoming “the first movie studio to surpass $1B in domestic box office receipts for 11 consecutive years.”

Anita Elberse, Harvard MBA Professor and author of Blockbusters: Hit-Making, Risk-Taking, and the Big Business of Entertainment, calls Alan Horn “the first person in the film industry to show that this resource-allocation strategy worked.” While these big event movies mean higher production costs, according to Elberse, “smart executives bet heavily on a few likely winners. That’s where the big payoffs come from.”

Here are some of the other popular methods studios have employed as they developed what is regarded as today’s film franchise model:

Here are some of the other popular methods studios have employed as they developed what is regarded as today’s film franchise model:

Innovative Marketing and the Cultivation of Anticipation

Innovative Marketing and the Cultivation of Anticipation

Jaws may have been the first to practice the now-standard method of cultivating anticipation, with nightly television advertising and Jaws-themed ice cream flavors, but a better example is the 1989 release of Tim Burton’s Batman, which marked the beginning of one of the most successful film franchises to date.

Today’s teaser trailers (for Batman, audiences paid full admission price to see the trailer on the big screen), limited run previews, character reveals, and cross-promotional saturation take a page from this movie’s strategy. Forbes film analyst Scott Mendelson deemed the movie “a machine of anticipation, hype, and preordained success.” Unofficially called “Bat-Mania,” the summer of 1989 mastered the high-concept movie release introduced by Jaws.

Established Value in Other Domains

Established Value in Other Domains

In Elberse’s analysis, she notes that while at Warner Bros. Horn often developed event films for the studio based on “properties that had already established their value in other domains.” For example, the proven success of the Harry Potter books lessened the risk of adapting them into big budget films. There was already strong character identification among potential viewers and a proven fan base.

Established value also works by utilizing cross-promotional merchandising featuring characters which have access to multiple media genres with already-established fan bases. This means that a video game or live stage show based on Marvel characters is also acting as an advertisement for the Marvel brand, and ultimately, for the next Marvel Universe movie. The Pirates of the Caribbean, one of the highest grossing film franchises, established its value as a Disney theme park ride before being adapted into a hit summer film.

Branding

Branding

Author Craig Lambert pointed out in an article on Elberse in the Harvard Review that “branding is one way to bring familiarity and repeatability to the volatility of the marketplace.” Brand names can also generate multiple streams of revenue from a single source.

Hollywood stars are often leveraged as a form of branding. Many stars now sign the contract for the film sequel and/or prequel before the first movie in the series even hits the theater. Branding also creates the possibility of ancillary businesses, which in turn fuel popularity of existing films (much like established value). This works as a self-fulfilling prophecy for a brand.

Robert “Bob” Iger, Chairman and CEO of The Walt Disney Company, says the “focus on brands is all important. I believe that in a world that was getting far more complex in terms of distribution…the value of brands, if well nurtured, would only increase.” Mr. Iger is credited as the executive responsible for creating content around established brands, and for turning Disney into more of a franchise-focused powerhouse.

Intellectual Property

Intellectual Property

The Marvel Cinematic Universe and DC Comics have the most robust slates of all the franchise films. The reason for this deep pipeline of upcoming film material is that they have libraries of seemingly endless characters and storylines to draw from.

These characters have such clout that when Marvel set out to attain their independence from big studios in 2007, they used characters from the Marvel Universe library as collateral in their negotiations with Merrill Lynch.

In 2014, Warner Bros. feature films crossed the $4 billion mark in worldwide box office for the sixth time, a success led by franchise films. Their current slate is their most ambitious yet, with at least 10 films based on their intellectual property including the DC Entertainment library and the Harry Potter series.

Creative Talent

Creative Talent

Bob Iger of Disney acquired Pixar Animation Studios in 2006 for $7.4B, Marvel Entertainment in 2009 for $4B, and Lucasfilm for $4.05B in 2012. These major acquisitions were desirable to Disney because they came with some of the most developed creative visions in the industry. In addition, these brands could be extended to every facet of the Disney business–theme parks, consumer products, and live action shows.

Warner Bros.’ anticipated follow-up films in the Harry Potter series, Fabulous Beasts and Where to Find Them, are based on the Hogwarts Academy textbook, and the screenwriter is Harry Potter author J.K. Rowling herself. Last summer Warner Bros. created the Harry Potter Global Franchise Development team, with the purpose of developing and executing a “high-level strategic vision for the Harry Potter brand” in collaboration with author Rowling.

The pairing of young, visionary directors with pop culture narratives is another way creative talent contributes to the success of franchise films. Today, directors like J.J. Abrams (December 2015’s Star Wars: Episode VII–The Force Awakens), Christopher Nolan (2005’s Batman Begins), and Alfonso Cuarón (2004’s Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban) are able to bring complexity to established stories.

These directors also function as a form of branding for a franchise, drawing fans of the director’s work even when the brand or character is unfamiliar to them. Lending artistic relevance to event films also increases the likelihood of attention during awards season, and big awards mean bigger box office revenue.

Investment in Production Value

Investment in Production Value

If a studio budgets big for their tent pole films, Horn determined that in the movie business “the product is the same price to the consumer regardless of the cost of manufacturing it…whether its production budget is $15 million or $150 million…so it may be counterintuitive to spend more money. But in the end, it’s all about getting people to come to the theater. The idea was that movies with greater production value should be more appealing to prospective moviegoers.”

According to the studios, franchise films being made today are meant to be experienced in the theater. At the 2014 Bank of America Merrill Lynch Media and Entertainment Conference, President of Walt Disney Studio Alan Bergman spoke with BAML analyst Jessica Reif Cohen about franchise management and branded content strategy. Bergman explained that Disney’s focus on “big branded movies” includes a desire that people see these movies in the theatre.

Forty years after Jaws, Hollywood just concluded its second-strongest summer ever at the domestic box office. Highly-anticipated fall and winter releases include the new James Bond film Spectre, The Hunger Games: Mockingjay Part 2, Pixar’s latest tour de force The Good Dinosaur, and December’s surefire seat-filler Star Wars Episode VII: The Force Awakens.

Sources

Bergman, Alan and Cohen, Jessica Reif. (2014, September 17). Bank of America Merrill Lynch 2014 Media and Entertainment Conference. Interview. Retrieved from http://cdn.media.ir.thewaltdisneycompany.com/2014/events/ab-baml-2014-0917.pdf

Garrahan, Matthew. (2015, May 22). Disney: Let it grow. Financial Times. Retrieved at http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/26f154de-005f-11e5-b91e-00144feabdc0.html#slide0

Garrahan, Matthew. (2014, December 12). The rise and rise of the Hollywood film franchise. Financial Times. Retrieved at http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/2/192f583e-7fa7-11e4-adff-00144feabdc0.html

Lambert, Craig. (2014, January/February). The Way of the Blockbuster. Harvard Magazine. http://harvardmagazine.com/2014/01/the-way-of-the-blockbuster

Mendelson, Scott. (2014, June 23). Tim Burton’s Batman at 25, And Its Wonderful, Terrible Legacy. Forbes. Retrieved from http://www.forbes.com/sites/scottmendelson/2014/06/23/tim-burtons-batman-at-25-and-its-wonderful-terrible-legacy/

McClintock, Pamela. (2015, August 4). North American Box Office Revenue Hits Record Levels Year-to-Date. The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved from http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/box-office-revenue-hits-record-813150